From the moment I decided to write this book, there has always been a question of whether it was titled “The Only Time Richard Got Angry at Me,” or “One F of a Coincidence.” Because while it started with that one moment with Richard, it is perhaps more a story of a crazy coincidence. Several actually, across my lifetime.

This book will indeed cite new information and may very well solve the case of The Zodiac Killer, the serial murderer who terrorized San Francisco and the Bay Area in the late 1960s and early 70s with taunting letters and codes accompanying grisly murders. The media-craving, or perhaps more correctly, the media-savvy psychotic killer, even knew to give himself a name to add to the hype. Now with literally millions of people following the case, and thousands trying to crack it, The Zodiac is arguably the most famous remaining cold case of the 20th century.

It seems prudent to write something here, in the beginning of this book, explaining that I will be writing about many things other than Zodiac—like the humor, hi-jinks and pranks at the Stanford Chaparral and their rival, the Stanford Daily, the smoke-filled offices of Madison Avenue, concepts in cognition and interspecies communication with pioneering scientist Dr. John C. Lilly, work with Japanese media company Digital Garage, underground psychedelic rave culture and more.

This is a story of coincidences, strange, decades-long coincidences.

So much of my life has involved alternative communications; jokes and pranks, national advertising billboards, television broadcasts using “virtual reality” (both in the traditional and non-traditional sense), computer coding, interspecies communication with dolphins, and also dogs, cats, sheep, pigs, ducks, crows and more… I don’t think I would have been able to comprehend what I was looking at without my previous experiences, which all play a role in this tale.

I was born a farmer and have worked as a banker, performed at Montreux Jazz Festival and on Dr. Demento. Puns and wordplay are my afflictation. I have experience pulling pranks; have attempted to create a language both humans and dolphins could speak; have experimented making codes and ciphers. I have hidden secret art in other art, and left Easter eggs in publications.

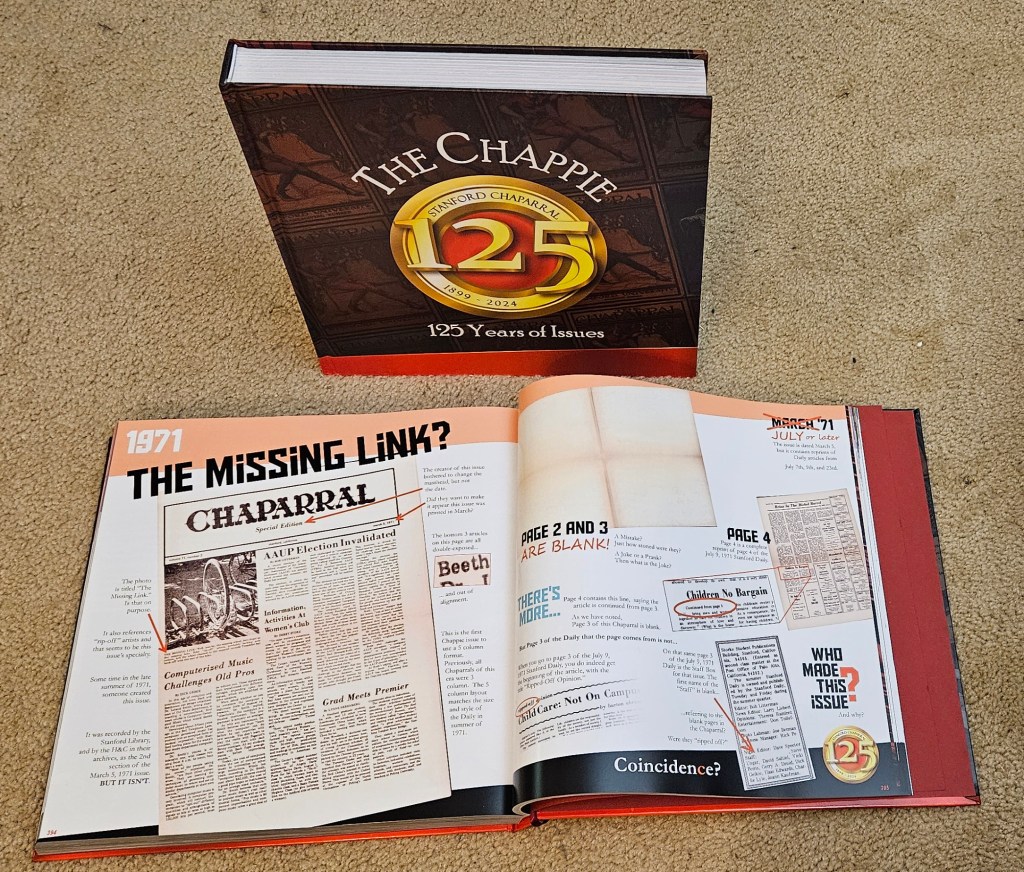

And even after all these years, I still call myself a Chappie. A “Chappie,” in this context, is a member of the Stanford Chaparral, the humor magazine of Stanford University, sort of a west coast Harvard Lampoon just without a castle. I called myself a Chappie in 1986, and in 1994, and in 1999. When The Onion asked me in 2002 for a name to accompany my photo in their article “Stoner Uncle All Kids’ Favorite,” I gave them the name of Chappie legend Mike Dornheim. I still called myself a Chappie in 2006 when Dornheim saw me for the first time since the article and said “You die,” and I still am a Chappie in 2024. I fully agree with the Chaparral motto, “’tis better to have lived and laughed, than never to have lived at all.” The people I have known through working on the Chaparral are some best and most creative one can ever hope to meet.

That said, I am not the first person to observe that Chappies seem to have some strange, random, psychic power, or, just the ability to foolishly wander into events in bizarre and comical ways. It seems to be happening again.

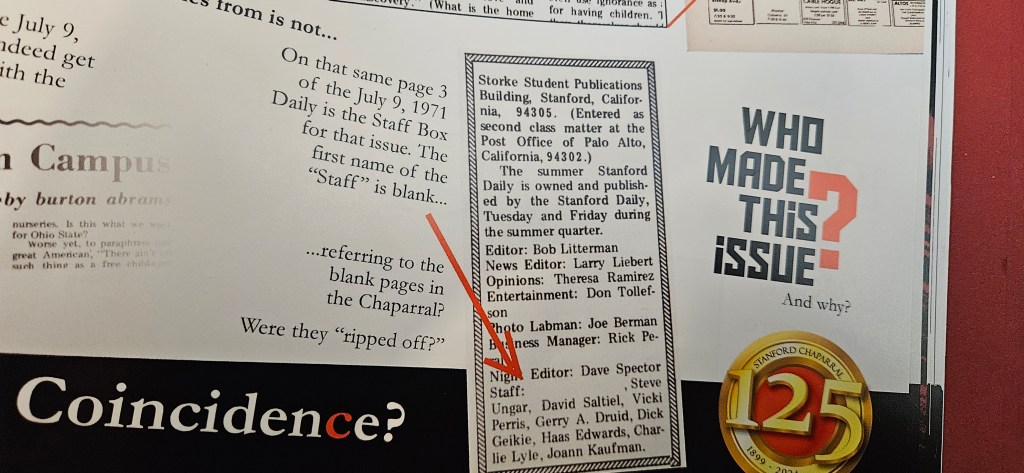

So yes, I knew Richard Gaikowski, and that started me down this path, but it was only because of my life experiences that I could recognize what I was seeing. And only because I was a Chappie that I bumbled upon the key discoveries. Who would believe that through the Chaparral would be the path that might solve this mystery? And that the Stanford Daily, the student newspaper of Stanford University, was also central to this tale? It’s quite a bizarre concept to get one’s head around. The long running rivalry and sometimes contentious relationship between these two Stanford student publications would make this story comical, if not for the seriousness of the subject at hand.

I would like to suggest that Zodiacifiles regard this book like one might the John Lennon / Yoko Ono album Double Fantasy (that might be better called Love is Deaf). Other than writing a bad review for it, the best strategy for that album is just to listen to the tracks you like. For such readers I recommend Acts II and V of this book.

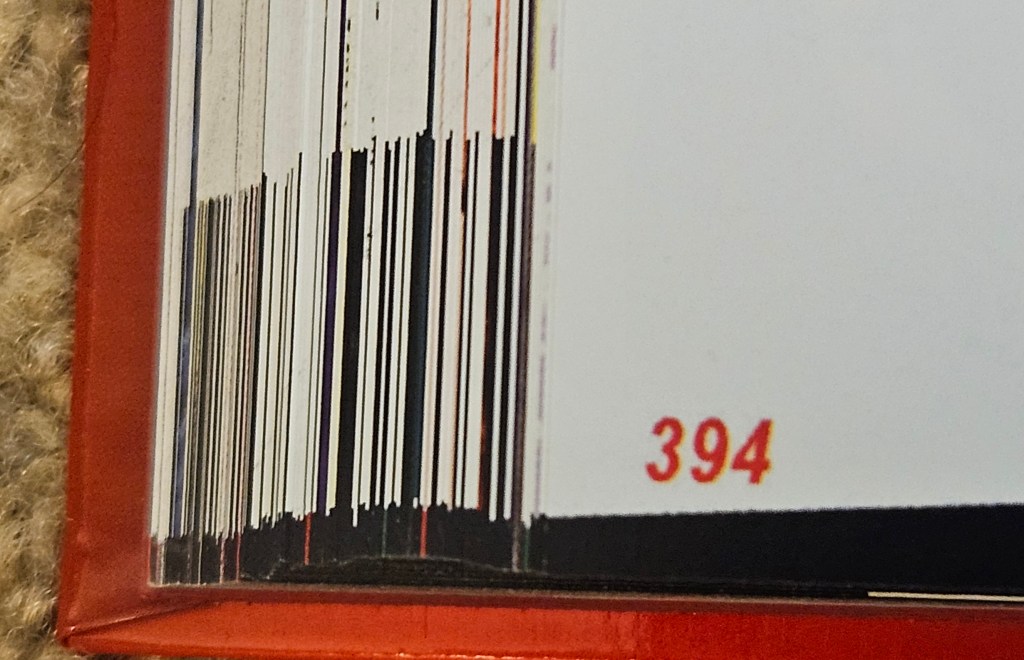

There is also a huge reason to write more rather than less: This is still a cold case. No one knows what is relevant or not. And while you can indeed hide a tree in a forest, even unintentionally, at least the tree is there. (In the book, The Chappie – 125 Years of Issues, you can find that tree on page 394.) On the other hand, it would be a tragedy if the tree inadvertently happened to end up on the cutting room floor. If the conclusion to this story is anything like the beginning and middle of it, then there is likely a big sequoia or banyan right in the middle that I haven’t seen, that we all have missed. Someone out there knows more about the tale I’m about to tell, and even crazier, they may not even know that they know.

While some existing dots may be connected, this book starts a whole new page of dots previously unknown to the public. Synapses will re-fire. The shroud of the years will fall off. And whether your metaphors are trees or dots, it should be interesting. Quite.

My own wonderment at this particular vista is a feeling somewhat beyond description. Before last year I had not written any book, now I will have produced two. And while I would have believed that I might one day produce a coffee table book about my beloved Stanford Chaparral, I would have been hard pressed to believe I would write a book such as this one. I would have been even more incredulous at the idea that I find possible clues to a crime in actual Chaparral and Daily issues, and even completely unbelieving that I would reprint those key clues in that huge Chappie anniversary book.

But I did.

It happens every day. Right?

Leave a comment