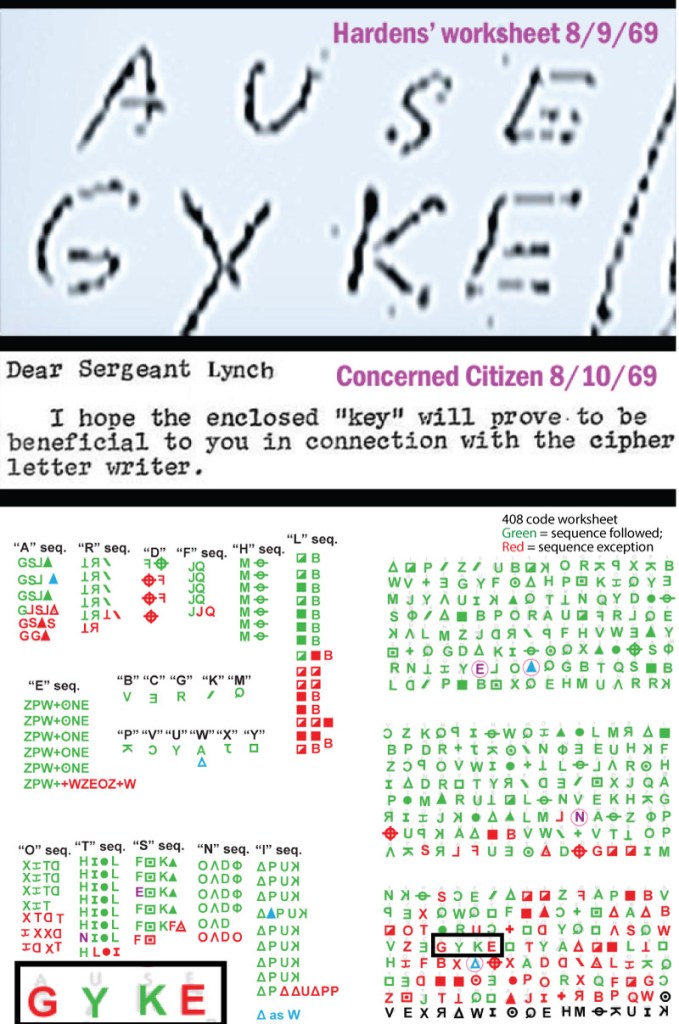

SUMMARY: It’s not just that GYKE appears in the code, but that those four letters cipher to AUSE. And one day after the Hardens solved most of the code (except for the last 18 letters) someone calling themselves “Concerned Citizen” also sent in the solution to the code (except for the last 18 letter), strangely putting the word “key” in quotes.

Book excerpt:

The 408-code is often described as solved, but in reality, it is only partially solved, the final 18 characters are still unknown. Furthermore, if we believe the killer to be truthful, his identity should be in part three of this code. Is it in the 18 unsolved characters, which happen to reside in part three? Is it, as others maintain, the GYKE sequence of letters?

There is a lot of debate about this online. Frankly, I was tired of reading the back and forth and decided to do my own analysis of the code. For clarity, and because details are important, let’s do a quick review of the facts.

As we know, the Zodiac’s 408 Cipher was divided into three parts, and sent to three different Bay Area newspapers, Gibson Publishing, the owner of the Vallejo Times-Herald; the San Francisco Examiner; and the San Francisco Chronicle, on July 31, 1969. This was nearly four weeks after the July 4th murders, and about eight weeks before Lake Berryessa. Each mailing also included a letter demanding that the enclosed code appear on the front page of the paper the following Friday, or else he’ll go on a killing spree.

Part one of the code was sent to the Vallejo Times-Herald, which sort of makes sense. After all, so far all the murders had occurred in that area, why not start there? The second letter was sent to the San Francisco Examiner with identical text, along with Part two of the code. Part three of the code was sent to the San Francisco Chronicle, with a letter identical to the other two, EXCEPT the added line, “in this cipher is my identity.”

On the fourth line of the third part of the 408-code is the four-letter sequence GYKE. Richard called himself Gaik, authored articles as Dick Gaik and D. Gaik. I have read some accounts that he also spelled it Gike, but I have never been able to independently verify that.

In no known byline or other writing did he spell it Gyke. This is a very important point to those who discount Richard Gaikowski as a Zodiac suspect. To those who think Richard is not Zodiac, GYKE is just a coincidence.

Yet again we have circumstances that are either relevant, or just coincidence. And possibly One F of a Coincidence, because it’s not just that GYKE appears in the code, but that those four letters cipher to AUSE. Hey, maybe it’s all a coincidence.

Now consider the possibility that he wrote under the name Geikie. When you have an EI or an IE in some languages like English or German, the second letter determines how it is pronounced. Geikie rhymes with spikey. Geik rhymes with bike, Mike, and…Gaik.

On the other hand, Geikie is a Scottish name, and they pronounce it with a hard E: geeky. It’s worth noting that the Scottish pronounces both the EI and the IE in Geikie as a hard E. And while I could find no direct reference for Polish, the ethnic background of Richard, his name contains AI that is pronounced as hard I. So, it is a reasonable conjecture that he would pronounce the EI in Geikie the way he pronounced the AI in Gaikowski. Regardless, punsters and word-jokers use both spelling and pronunciation to make their jokes.

Those who discount GYKE in the code, saying he never spelled it that way, seem to miss the point that it is phonetic. The foundation of puns play is with phonetics—two words that sound the same or similar, creating a joke. GYKE is a phonetic match to “Gaik,” as is AUSE to “ows.”

My final point to those who discount GYKE in the 408 cipher: Can you imagine if Richard was Zodiac, and he indeed wrote GAIK in the cipher, and had it solve to OWSK? I mean, why bother with a code at all? Why not just confess? If you made it that easy, it would be the equivalent to a confession. Of course you would not do that. One also would not use the name Gaikie, as it would be too obvious, to close to Gaik.

In this cipher is my identity

The 408-code was mostly solved in just a few days. All of part one. All of part two. And almost all of part three. Of the eight lines of part three, only the first seven lines, minus the last letter of line seven, have been solved, leaving the 18 unsolved characters.

When the code was broken, by Don and Betty Harden, they wrote “signature” over the last line. Of course, they thought this must be where Zodiac encoded his name. He had written that this cipher contained his identity no less, so it was obvious. Right? It was a very logical assumption that those final 18 letters were indeed where the identity was, and the killer had changed the code for them to make it harder to crack. My god, anyone could see that.

This final line of the 408-code remains unsolved to this day. Using the same cipher as the rest of the code, it reveals gibberish. So, it is either encoded differently than the rest of the message, is some kind of anagram or component word, or is indeed gibberish.

In the MysteryQuest TV show about Richard, Blaine plays audio that he claims is Richard. As I have said previously, it sure sounds like Richard to me. In the audio clip, Richard talks about the military sending gibberish codes to throw the enemy off.

So I ask, if you were going to hide your name in a cipher, and you really didn’t want it to be cracked, might a line of gibberish at the end be the perfect thing to throw people off the trail?

I know this contradicts the thinking that the Zodiac was indeed truthful, but I’ve only conjectured that he was mostly truthful. Moreover, it doesn’t have to be all one or the other. By his own writing, Zodiac is aware of the concept of leaving “fake clews” as he spelled it.

Part three of the 408-code is high stakes, he’s putting his name in there. He needs to make sure it is not too easy. Outside the box thinking would be called for. Adding in the bogus letters would create some added insurance to throw people off the trail.

And it is a certainty that Zodiac wanted part three of this code to be harder to solve. How can I say it is a certainty? The breakdown of the 408-code in the next section will show that very simply.

408-Code Deep Dive

I decided to break down the code myself, and diagram how it was constructed. From that, I would be able to comment on it free from the noise of 50 years of debate. This process greatly increased my understanding of Zodiac’s coding methods, and allows me to state the following opinions on this with cautious confidence.

It is indeed a certainty that Zodiac wanted part three of the code to be harder to solve. We know this by how the code is constructed. This code is not a simple letter-substitution code. For most of the letters, Zodiac used more than one symbol, substituting them in a sequence. For example, the letter E is encoded with seven different symbols: Z, P, W, +, O, N, and E, in a repeating sequence. Starting in cipher part one, the sequence repeats five times perfectly, but on the sixth time, one line above GYKE, it goes awry: Z, P, W, +, W, Z, E, O, Z, +, W.

This pattern of sequences repeating perfectly for a while, before being modified at their end is consistently replicated for other letters: S, I, A, H, R, L , T, N, and O. The letter E has the longest sequence, using seven letters, many others have four letter sequences, some have three or two, and a few letters use just one letter.

The effect of this is that, with a couple of exceptions (that might be mistakes), part one of the code is entirely consistent; part two is almost entirely consistent, with a few exceptions starting at the bottom of this part of the code; but part three is VERY inconsistent. It is clear that Zodiac wanted part three of the code to be harder to crack, and/or he was making exceptions so as to force another message into the puzzle.

Here’s the thing, if you did want to do something like encode your name in both the puzzle and the solution of your code, it wouldn’t be the easiest thing to do. As I found when making my Berkeley Bear code, it was hard to not have unintended consequences. You could not just change a letter, without checking to see how it affected all the code. One would almost certainly have to make exceptions or do some kind of rigging to make the code work out.

In plain English that means you would likely have to make exceptions in your coding rules to make the joke happen. If the Zodiac’s name were indeed in the third part of the code, there would likely be evidence of exceptions or inconsistencies in it.

But this would be a tricky operation. If your exceptions were too clunky, you might very well give yourself away. The perpetrator might actually tip their hand by showing WHERE the exceptions occurred. So I conjectured that the substitutions would be numerous—helping to camouflage the key ones, in part three of the code. I began my diagramming of the code in earnest.

I decided to color-code the solution: very light grey when the code followed its rules, meaning when a letter was encoded in its established sequence. When a letter did NOT follow the established sequence, it is colored black. When there was something I did not understand, or a possible mistake, I marked the symbol in a dark grey. The 18 unsolved characters at the end I put in white with black outline.

When you apply the shading, the point about exceptions becomes obvious.

You can clearly see that the top section has no code exceptions, save for the possible mistakes. The second section begins that way as well, but starting with its final lines there is a large increase in the exceptions. The exceptions continue into the third section of code, which becomes mostly exceptions. Most of the letters in part three that are light grey are those where only one symbol was used to encode the letter, so of course they stayed consistent.

The last 18 characters remain uncracked, seemingly unrelated to the rest of the code. At minimum it uses a different cipher, or has an additional filter, or is an anagram. Or perhaps it is just gibberish to throw people off.

This exercise shows that effort was being made in part three of the code. Why would one bother to switch all of those letter sequences for no good reason? Perhaps just wanted to F with people, maybe just to throw people off the trail. The fact remains that GYKE didn’t have to appear, both the G and the E were exceptions to their letter sequences. Without such exceptions, GYKE should have been SYKZ.

The tricky part of this, or perhaps the prank part, is that I’m sure everyone initially thought that the name would be revealed when the cipher was cracked. That was their first take—solve the cipher and the name would be revealed. When it wasn’t there, people didn’t accept it, and got the idea that Zodiac was lying.

When combined with the fact that the 340 code, which for decades people believed a fake code and used as evidence of the Zodiac lying, was actually a real code, I began to come to the opinion that Zodiac was mostly truthful.

Either way, because of the numerous code substitutions in part three, and the 18 unsolved characters, it is my opinion that the identity of the Zodiac is indeed in there, whether it’s GYKE, or someone else.

Conjecture: The 408 Code is indeed solved by the Concerned Citizen letter

All through the past couple years the debate, and joking about when and when not to use quotes, double-quotes, single quotes, quotes for titles, quotes for jokes, quotes for quotes, and the various meta meanings for quotes, including in legal documents and consequences, has been central to our lives, including the Chappie book and zoom calls, the writing and editing of this book and any and all parts of daily conversation.

In that context, I would just like to ask why the Concerned Citizen put quotes around the word “key” in his August 10, 1969 letter that contained a correct solution to the 408 code? I conjecture that it is because “key” is special. “Key” isn’t really the key to the cipher, it is the “key”. In my opinion as a prankster and wordsmith, I agree with those who posit that GYKE solves to AUSE when you have the “key.” This opinion has been around online for years, I only note that if Richard Gaikowski is indeed confirmed to be the perpetrator, this is certainly what is meant by “In this cipher is my identity,” in the letter to the Chronicle accompanying part 3 of the code.

In the 1971 Stanford Chaparral “Missing Link” issue, the fake, planted prank issue contains the byline “Dick Geikie.” Is the intended pronunciation, GUY-KEY? Is this a joke reference to the Concerned Citizen letter? Is “Geikie” proof that Richard used variations of “Gaik?” Does “Geikie” make “GYKE” from the 408 code more plausible as another variation? All of these new questions only deepen the mystery, but do add support those who have pointed to the significance of “GYKE” in the 408.

Leave a comment